Vinyl manufacturing

Knowing how vinyl records are manufactured is essential in understanding and interpreting matrix codes, which again can result in more information about the records. This is not a detailed description of the process of vinyl production, vinyl quality, and so on, but a short overview to understand how and when matrix codes are etched into the run-out grooves.

Mastering: Lacquer

The recorded music is transferred from the master tape to a lacquer-coated aluminum disc by a lathe. The audio is cut with a corundum (sapphire or ruby) cutting stylus. This is the opposite of playing the vinyl record; you feed audio in and get mechanical motion out, cutting the grooves. In this process, the settings also have a great influence on the sound. The result is two master discs, one for each sides A and B. There are several names for them; masters, soft masters, lacquers, and they are also sometimes incorrectly called acetates. On this site they will be referred to as lacquers. [1] The lacquers can be played back, but doing so would degrade the quality. The lacquers are refridgerated for preservation if they are not going to be processed right away. [2]

A set of reference lacquers for listening can be cut on a slave lathe in tandem with the master lathe, but the audio may be slightly different due to the different lathes [3]. Typically, only the Americans used tandem lathes. Reference lacquers are cut only when the client asks for them or the cutting engineer wants to point something out to the client before cutting the actual production lacquers. [4]

A cut lacquer looks similar to a black vinyl record, but it is larger then the record it will produce. For example, 7" records are always cut on 10" lacquers [4]. Lacquers have a second peg hole to avoid slipping on the lathe while cutting. Sometimes adhesive labels are placed on lacquers. If so, they will cover the second peg hole. Image 1 shows a Bleach reference lacquer cut by Heathmans Mastering.

1. Bleach reference lacquer by Heathmans Mastering, adhesive labels

Processing: Fathers, mothers, stampers

The lacquers are put in baths and electroplated with nickel. Once completed, the metal is separated from the lacquers with a blow of a special hammer. The lacquers are most often destroyed in this process. The resulting metal plates are called fathers, masters, or matrices. They are negative images of the lacquers, and cannot be played. They can be used to press vinyl records, but only if a small quantity is required. [1] Metal plates degrade with use, and will start to wear out after about 1000-1200 records pressed [5,6]. You could cut several sets of lacquers, either individual cuts or cuts by slave lathes in tandem with the master lathe, and electroplate them to create several sets of fathers to use for pressing, but you can also process the fathers further [1].

The fathers can be electroplated to form a set of mothers. These are positive images of the lacquers, so they can be played for testing, but obviously they cannot be used for pressing records. The mothers are electroplated again, and the resulting negative images, stampers, can be used for pressing. [1] The fathers and mothers can be electroplated several times, though there is a limit, about six times, before they degrade. In this case, 36 sets of stampers can be made from one set of fathers, and about 36,000 good quality records can be pressed. Several sets of lacquers must be created if larger quantities are required, although many plants press well above the recommended numbers. [7]

Image 2 shows a side B stamper for the MFSL release of Nevermind on top of its sleeve, and a part of the matrix code. Pressing plates used to press the Kill Rock Stars compilation can be seen on nirvana-discography.com.

2. Nevermind MFSL side B stamper and matrix code

Alternative: Direct metal mastering

It is possible to eliminate the two first processing steps by cutting a set of mothers directly on copper plates. This is called direct metal mastering (DMM). A large amount of stampers can be processed from the copper mothers directly, but if very large quantities are required, a stamper can be plated to create a new mother, wich can then be plated to create more stampers. [8] Image 3 shows a copper plate being cut using DMM. DMM discs are cut with a diamond cutting stylus. Lacquers are never cut with a diamond stylus. [4]

3. A copper plate being cut using DMM

Pressing

Vinylite pellets are heated and turn into molten slabs called biscuits. A label is placed on each side of a biscuit, which is then placed between the stampers mounted in the press. The pressing plates are heated with steam as they are pressed together, allowing the vinylite to flow into every groove, and then quickly cooled with water, and a vinyl record is made. [1] Pressing takes about eight to nine hours for 1000 records [6].

Picture discs are made on manual presses [4]. They consist of three layers of vinyl, with the two images put inbetween the vinyl layers. The outer layers are clear vinyl, while the middle layer can be any color. In image 4, it is blue. However, test pressings for picture discs are usually done as regular black vinyl pressings. [2]

4. Picture disc with blue vinyl in the middle layer

These two videos on Youtube.com show the process from mastering to finished records. Note that they omitt some of the processing, and use the first metal plates, the fathers, as stampers: How vinyl records are made part 1, part 2.

Mixed colors

Ocassionally records have traces of other colors, as the three different Molly's Lips singles shown in image 5. If the hopper and extruder where the vinylite pellets are melted and formed into biscuits are not cleaned between changing colors, remains of the previous color will mix with the new color, fading for each record pressed until it has been completely purged from the machinery [2,4]. Also, the biscuits are sometimes composed of a mix of virgin and recycled vinyl, which can lead to smaller impurities, which can also end up becoming a quality issue [1]. In the case of the singles shown in image 5, it is obviously the first scenario, as the effect is quite severe. It seems they made no effort to clean the machinery between colors, instead just letting it clean itself with the green vinylite pellets.

5. Impure Molly's Lips pressings

Matrix codes

Text and numbers may only be added to the run-out groove on positive images, in other words on the lacquers and on the mothers [7]. The stage which the text was etched can be observed, as text etched into the lacquers will be deep and smooth, while text etched into the mothers will be shallow and uneven. Text can only be etched into the mother plates when using DMM, meaning it may be hard to determine whether text was etched by the mastering facility or processing plant. DMM matrix codes usually looks similar to matrix codes etched into lacquer, though perhaps not so deep.

Some times one company handles the entire process of cutting the master (lacquers or copper plates), processing, and pressing, but in most cases there are different companies which handle each job. The mastering studio will often write or stamp the catalog number, side A and B information, the name of the mastering facility, internal job number, the signature of the mastering engineer, which plant which will receive the lacquers, and perhaps a funny comment. If a cut ends up being unsuccessful, which will in most cases be discovered after test pressings are made, a new cut will be made with "RE1" written in the matrix code, meaning recut 1, and similar for recut 2 and so on [7]. These parts are written into the lacquers or copper mothers, and are deep and smooth.

Occasionally the processing/ pressing plant will also add parts to the matrix code, such as their internal job number or the plant name. If they have to remake a mother, they may also etch "RE1" for remake 1 into the matrix code. If these parts are written on the nickel mothers, they can be told apart from the mastering engineer's parts as they are shallow and uneven. However, in many cases the processing/ pressing plant will write their parts into the lacquers, too, prior to plating, such as the L-codes done by Lee Processing [6]. In these cases only knowledge of the companies' different matrix parts can tell whether they were written by the mastering studio or the processing plant.

Usually the mastering engineer writes their parts into the run-out area as mentioned. Additional information can be inscribed around the outer edge, outside the music area of the disc in larger handwriting that is easier to read. This area is trimmed off of the stampers before pressing, and is only used to identify the source during processing. [4] However, there are some cases when the mastering engineers only wrote the catalog number and side information around the outer edge of the lacquers to keep track of which lacquer is which prior to plating, and nothing in the run-out area. In these cases the pressing plants wrote or stamped the entire matrix codes in the run-out grooves. [9]

This was common in the UK, at least at the time when Nirvana was active. Multiple records cut by different mastering studios but processed and/ or pressed in the same pressing plant have been found with identical handwriting in all parts of the matrix codes. Noel Summerville, who worked for many studios at the time, including cutting a few Nirvana records at Utopia, said he only wrote the catalog number and so on in the outer area, while the pressing plant would usually write the matrix code in the run-out area [9].

Matrix code example: American and French pressings of Oh, The Guilt 7" singles

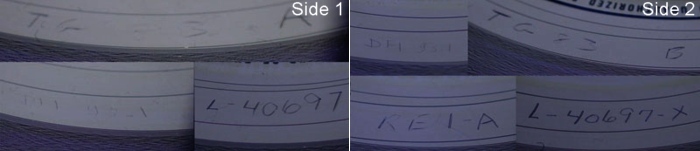

The American and French pressings have some identical parts in the matrix codes. They are partially shown in images 6 and 7 and transcribed below. The American matrix codes:

- Side A

- TG 83 A L-40697 R-15194

- Side B

- TG 83 B RE1-A R-15195-RE-1 L-40697-X

The French matrix codes:

- Side A

- DFI 93-1 TG 83 A L-40697

- Side B

- DFI 93-1 TG 83 B RE1-A L-40697-X

6. Oh, The Guilt US matrix codes

7. Oh, The Guilt French matrix codes

Approaching the problem methodically, the various companies involved and metal plates can be traced. The mastering facility cannot be identified from the matrix codes, but this is the least interesting aspect of this release. What we can see is that the two different pressings are sourced from the same set of lacquers. This is determined from the similar "TG 83" parts, as well as side B being recut as seen from "RE1-A". When the lacquers left the mastering studio, the matrix codes were simply:

- Side A

- TG 83 A

- Side B

- TG 83 B RE1-A

The next steps involve having some knowledge about what types of codes various plants etch into the run-out grooves. The L-codes were etched by Lee Processing [6], which is the next step in this example. It seems to be equally deep as the etchings from the mastering studio, so it appears that they etched the L-codes into the lacquers just before they processed a set of fathers. The L-codes are also completely identical on the American and French pressings, which means they could not have been etched into two different sets of mothers. Lee Processing also processed a set of mothers which they sent to the French plant, but whether the American plant received the set of fathers, or a second set of mothers processed by Lee, is uncertain. Regardless, the matrix codes are the same on the fathers and on the mothers, and also smooth and deep as so far all the parts have been written into the lacquers. The metal plates which left Lee Processing had the following matrix codes:

- Side A

- TG 83 A L-40697

- Side B

- TG 83 B RE1-A L-40697-X

The remaining etchings are clearly different to the text etched into the lacquers. They are much shallower and very uneven. The pressing plant in the USA, Rainbo Records, added the R-codes to the mothers [6]. The addition of the R-code and a second "RE-1" directly following the R-code, indicates that Rainbo received the only set of fathers from Lee Processing, and processed their own set of mothers. The original electroplating of the side B father must have been unsuccessful, and they had to electroplate the father again. The resulting side B mother was labeled "R-15195-RE-1" to indicate it was a remake.

The French plant, DFI, received one pair of mothers, into which they etched their initials and "93-1", either dating the manufacture to January 1993 (the single was released on 1993.02.22) or numbering it as their first project of 1993.

Other interesting applications of record production and matrix code understanding can be found in the test pressings section, most notably the pink test pressing of Bleach and the following recut of side B.

References

- [1] recordcollectorsguild.org (defunct)

- [2] Mayking employee

- [3] Thomas Pessagno, The Mastering Lab

- [4] Michael Papas, Australian record industry

- [5] erikarecords.com

- [6] Steve Sheldon, Rainbo Records

- [7] JG, mastering engineer

- [8] wikipedia.org

- [9] Noel Summerville, Utopia

- Image credits: Enrico Vincenzi (1, 4, 6-7), Jeremy Little (2), Elysia (3), Dave MacDougall (5a), Guido Maria Muscelli (5b), Cedric Vanoverstraten (5c)